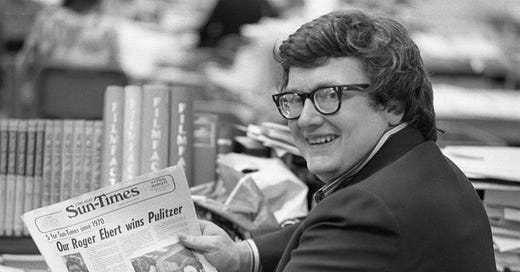

Back in 2008, a few years before Roger Ebert’s passing, he published his “little rule book.” These were tips of the trade—what to avoid, what to embrace, and what to be mindful of—that he thought every critic needed to know. If you’ve never read it, I highly recommend doing so. Some of the advice includes being suspicious of freebies, providing a sense of the experience and why you shouldn’t take photos with celebrities.

There is, however, one rule I continually return back to; and I usually read it slightly out of context: “Be prepared to give a negative review.” In this instance, Ebert was referring to watching a movie belonging to a friend. If you’re afraid that a well-articulated negative take will end your relationship with someone, then they never really were your friend, he explains. This usually goes for close associations with filmmakers, stars and below-the-line crafts people.

As a critic, I apply Ebert’s sage advice slightly differently. In general, you should always be prepared to give a negative review, whether you know the person or not. In your review you can make allowance for circumstances, you reason and try to understand the filmmaker’s intent, you can give praise for one component but dislike the rest—but these factors shouldn’t wholly be used as an easy out to not give a negative review.

In this regard, I think, I somewhat differ from some of my colleagues: I don’t believe a movie has to be outright bad to receive a negative review. If there are glaring weaknesses that significantly affect a person’s enjoyment of the film, therefore causing the final film to be significantly less than its perceived potential, then that’s enough for me to give a negative take. That doesn’t mean I go scorched earth on the movie (it’s misnomer to believe every review of bad movie must paint the film as atrocious). But I try to give a balanced take that ultimately explains the underwhelming components I could not look past.

While I don’t mean to paint my colleagues in broad strokes, I should point out that on the whole, Rotten Tomatoes scores are now inflated. Per Global News: “In 2009, the average Tomatometer score for all wide releases was 46 per cent, and it was roughly at that level for much of the 2000s. By 2019, that average score had climbed to a high of 62 per cent — an important milestone, since 60 per cent is the dividing line between a ‘fresh’ film and a ‘rotten’ one.”

There are quite a few factors that could explain this sharp rise: An understandable unwillingness to adversely impact marginalized filmmakers’ trajectory with a negative take, a skittishness by critics outside of a underrepresented community and culture to bash a film when they’re somewhat self-aware that they don’t have the range, the ever dissolving boundaries between critics and talent, the anger that can spring from social media, the maliciousness that arises from studios, inexperience, and so forth. I don’t think critics softening the edges of their reviews is ever a conscious decision. Most critics barely have any time to breath between watching the movie, reviewing it, and publishing their take. But unconsciously it probably happens more often than we’re willing to admit.

But wariness to give a negative review on the part of the critic naturally suffocates criticism. It withholds the intricate self-exploration, self interrogation and emotional and intellectual vulnerability that should occur while you’re writing. It dilutes the rawness of thought and the poetry of discovery. So how does one overcome it? There’s only one way: Always “be prepared to give a negative review.” Because ultimately, the only person who regrets not doing so, is the writer — it is you. And I prefer to think of my voice and my curiosities as unencumbered. It’s healthier, for myself, and the movie.