In many ways, my grandmother, my father’s mom, wasn’t your typical grandmother. She cursed; she gambled (she wasn’t wholly trustworthy). She deeply believed in God but I never saw her inside a church. She lived in Chicago for much of her life but she never ceased being a Southern woman. She was the only person my father truly feared, and one of the few people who garnered his full devotion. She wore a scarf on her head and loved hot sauce. She was short, overpowering, resourceful, resilient, sharp, wily — she was as blind as a bat, but also liked to pretend she was deaf — and was surprisingly caring and forgiving. On Wednesday, August 16, I learned that she passed away. Lillie Grey Daniels was 100 years old.

I can’t remember a time when my grandmother wasn’t around. She used to own a building on the near west side, close to the corner of Washington and Talman. We lived in an apartment there for the first few years of my life. Some dicey “investments” — the lottery — forced my grandmother to sell the building. Around that same time, my dad started an auto-parts store after the company he worked for, where he served as foreman, decided they would move operations to South Carolina (they gave him the option to come and train his eventual younger white replacement, for a pay cut, of course). By that point, he wanted to be his own boss.

Now, much like my grandmother, my dad did not have the best business acumen. The auto-parts store struggled to take off: He spent nights sleeping in the shop, working there 24/7, while myself, my mom, brother and sister (a second sister would come later), all slept in the same bed in my grandmother’s living room. In my grandmother’s living room, from her sticky, plastic covered furniture, I watched the Chicago Bulls win championships and heard about a weird guy who I thought was named after orange juice. I also got my first spanking, which came at the hands of my grandmother (when I heard Bill Withers sing about how his grandma’s hands “Used to ache sometimes and swell,” it had a different meaning for me). She gave me my first cup of coffee, handed me my first pocket Bible — which I read cover-to-cover, back before I became an atheist — and she watched Xena, Hercules, and Deep Space Nine with me. It took years before I learned, through drips of gossip, how my grandmother ended up in Chicago.

Though she was born at the height of the roaring ‘20s in 1923 in Amory, Mississippi; she also came of age during the depths of the Great Depression. Within 18 years or so she met my grandfather Titus (every first born son in my family is named Titus). They eloped after my father was born in 1941. Soon after World War II erupted; my grandfather joined the Navy; my grandmother was left to raise my dad. Part of what happens next is real and maybe a little bit apocryphal: My grandma Lillie did not wait for granddad to come back home. In those lean years, she fell for James Hampton. Word is that, Mr. Hampton — whom my dad affectionately called pops — got into an argument with a white man that necessitated the family packing up and driving away from Mississippi during the night to Chicago, lest they risk retribution.

My grandmother and father rarely talked about the hardships they experienced in the South: Dad often recalled lying underneath the house as the KKK rode past, and the difficult life of sharecropping. The two remained Southern to their core, they’d talk about Mississippi as though it was an otherworld, a place of rolling hills where they had hunted rabbits, rested by the river, fished, and felt the sweaty Southern air wrap around them like a warm blanket. They never lost their drawl or their turn of phrases; they kept their cackling laugh and passed it down to me. They also never stopped believing in the potency of family. Many betrayals occurred in the Daniels family, but when the time came, no one ever shirked from their familial responsibility to provide help, to provide care. It why whenever my grandmother hugged you, she’d say, Oh, baby.

At one point, around when I was 10, we were deeply impoverished, and for a time slept in a van. Dad experienced a massive heart-attack that nearly snatched away his life, and surely took the auto parts store. My aunt gave us shelter, my grandmother took my dad in as he recuperated, caring for him as though he were a child again. We’d often visit him as he slowly regained his strength. There are very few moments where I can remember my grandma Lillie being totally kind, not like the scrawny girl forced by life to toughen into a hardened woman. My dad always listened to what she said; even on his deathbed when she told him to eat after he’d stopped eating for days, for her, he took two bites.

I remember the day he died, in 2015, her coming to see her first born now dead. I can still feel the tight, warm way she grasped me in a hug, wrapped in silent prayer. Days later she wasn’t afraid to speak her mind when the funeral was going to hell. In her 90s, she remained as tenacious as when I was a kid.

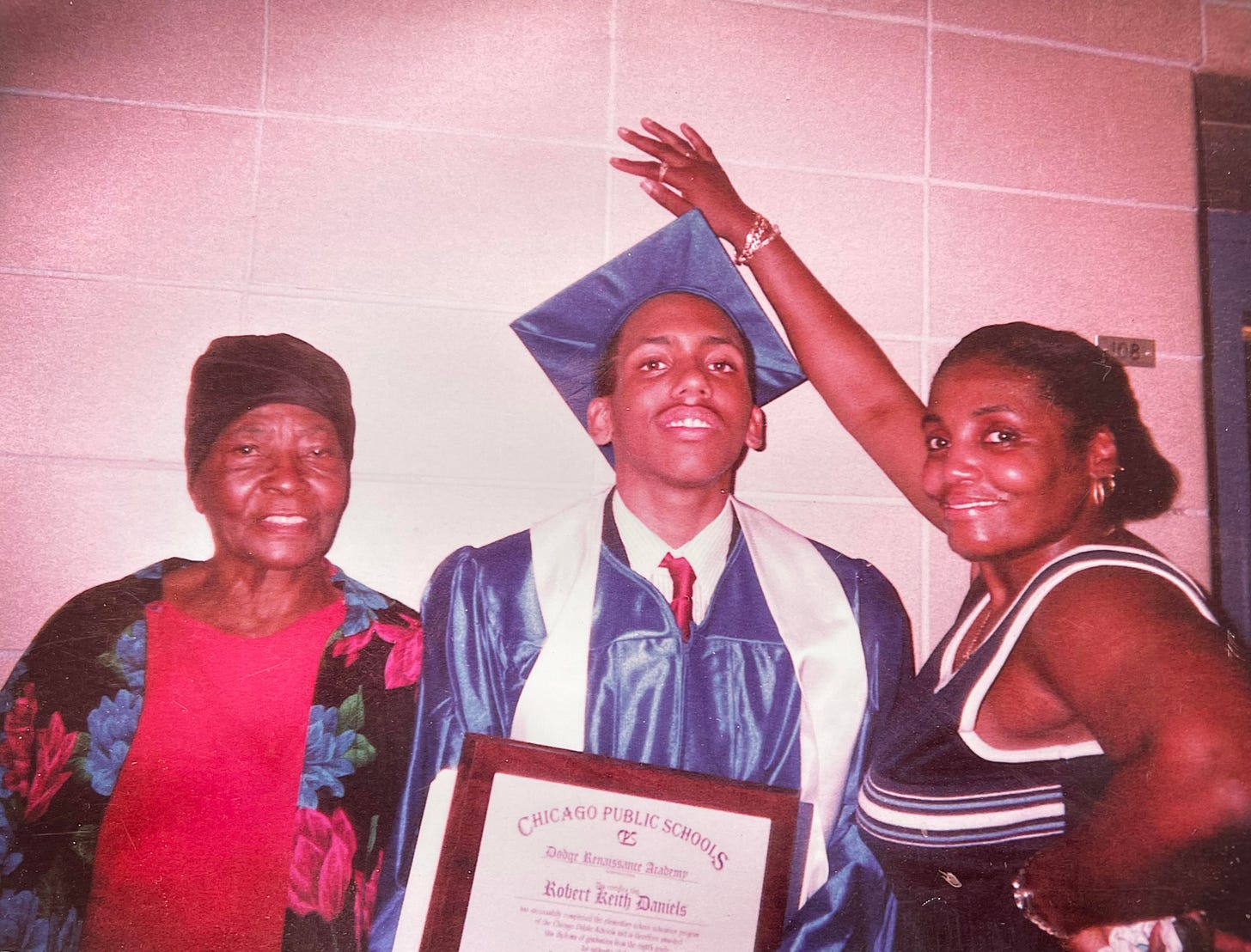

Over the last few days, whenever I’ve been caught in times of silence, I have thought about those bright passages and dark days my grandmother witnessed. She saw the roaring 20s, the Great Depression, Jim Crow South, the coming and the death of Martin Luther King Jr, Malcolm X, Fred Hampton, and Emmett Till. She saw the Korean and Vietnam War, Reaganomics, the AIDs epidemic, and September 11th. She also witnessed Civil Rights, Women's Rights, Gay Rights, the first Black American president of the United States, and the launch of computers, smartphones, and the Atomic bomb. She watched as my father begin in a one-room schoolhouse because of segregation and caught sight of her grandson earning a Master’s degree.

Grandma Lillie gave me shelter, history (the walls of her home were filled with pictures of the long gone), a sense of self, and a sense of suspicion and forgiveness, and she offered several lifelines that I’m still unwinding in my head. While on a car ride back home from Hyde Park, I remembered that when my grandmother first moved to Chicago she settled on the South Side. I’d like to think it’s because the area made her feel like she was still close to Mississippi, close to something familiar that she could still touch. I can’t help but think about what I’ve lost with her passing. She was one of the last connections to my dad; she was an archive of the Daniels family, a history that feels like it’s slowly slipping away deep into history’s unforgiving ether. Most of all, she is a portion of me; she is my calm, she is my temper, she is my single-mindedness. She showed me how to sit in meditative silence, and now that is the only place where she and my dad can come to me.

Beautiful. Thanks for sharing these words -- and your grandmother's story -- with the world.

My condolences, Robert. And a beautifully written tribute to someone who sounds like an impactful woman.