In a year where I took a small step back from writing to fill blind spots in my knowledge of film history, there were plenty of discoveries and first-time watches that popped up on my radar. These films are of course movies that, at the very least, predate 2021. They are 25 films that are inspiring in their approach, style and emotion. And I’m thankful to have finally caught up with them.

3 Bad Men, John Ford (1926)

Violent, vast, and visually sumptuous, John Ford’s silent epic about a trio of men of ill-repute, somehow, also contains a surprising tenderness.

A Man Called Adam, Leo Penn (1966)

I caught A Man Called Adam at TCMFF, my first, and I still can’t shake how amazing Sammy Davis Jr is as a troubled trumpeter navigating segregation opposite Cicely Tyson. Both actors are so giving as scene partners, yet never budge as emotional powerhouses. It’s a movie that confirms Davis as the most talented actor in the Rat Pack.

As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty, Jonas Mekas (2000)

Running at nearly five hours, this Mekas meditation affirms life not through seismic events, but through the everyday, mundane happenings of life that become seismic in our memory. Mekas’ wry, yet earnest narration — composed over images of his wife, his cats, and his children — is the stuff that dreams are made of.

Au Hasard Balthazar, Robert Bresson (1966)

I made the mistake of watching Au Hasard Balthazar late at night. I knew I made a mistake, in fact, within the first 10 minutes. Through the plight of a donkey we witness the cruelty of humans, and are, like the martyred religious journey experienced by Balthazar, forever changed. I will probably never rewatch this movie. Mostly because my first watch sent me through an existential spiral lasting two weeks. It is, of course, a tremendous film nonetheless.

The Big Parade, King Vidor and George Hill (1925)

One of the great pictures about World War I features John Gilbert as a soldier finding love and loss on the road to combat. No war flick has captured the hellscape of battle as well as this one, none have demonstrated the psychic shocks experienced by soldiers as well as this one does. Like Come and See, some of its images do not merely sear your mind, but tattoo onto your brain stem.

The Conversation, Francis Ford Coppola (1974)

Before seeing this at the Music Box Theater in Chicago, I’d seen enough bits and pieces of The Conversation to say I’d somewhat watched it. But this represented my first full watch in one sitting. Shifting and elusive, with an unforgettable sound design and performance from Gene Hackman, this surveillance film still feels prescient.

Days of Wine and Roses, Blake Edwards (1962)

A narrative confronting the disease of alcoholism when the subject was still taboo stars Jack Lemmon and Lee Remick who become so committed to the bottle, they flake from their daughter, their jobs, and even each other. Heartbreaking as it is honest, honest as it is heartbreaking, Days of Wine and Roses is as tragic as they come.

Dinner at Eight, George Cukor (1933)

Another TCMFF watch is this pre-code that features an all-star cast led by Jean Harlow. The dialogue snaps faster than a rubber band; the film moves as brisk as sweat against a breeze; and Harlow is a live wire dangling above a puddle, electrifying Dinner at Eight with her every scene.

The Earrings of Madame De…, Max Ophüls (1953)

The master of the tracking shot, this, the second to last work of his career, might be Max Ophüls’ best film. In it, a married aristocratic woman (Danielle Darrieux) falls for a dashing baron (Vittorio De Sica) behind her husband’s (Charles Boyer) back. To consummate their love, the baron gifts a pair of earrings to her that once appeared worthless. Can their romance survive with her husband lurking nearby? Brimming with tension and gorgeously articulated by Ophüls’ unparalleled camerawork, it’s a melancholic romance for the ages.

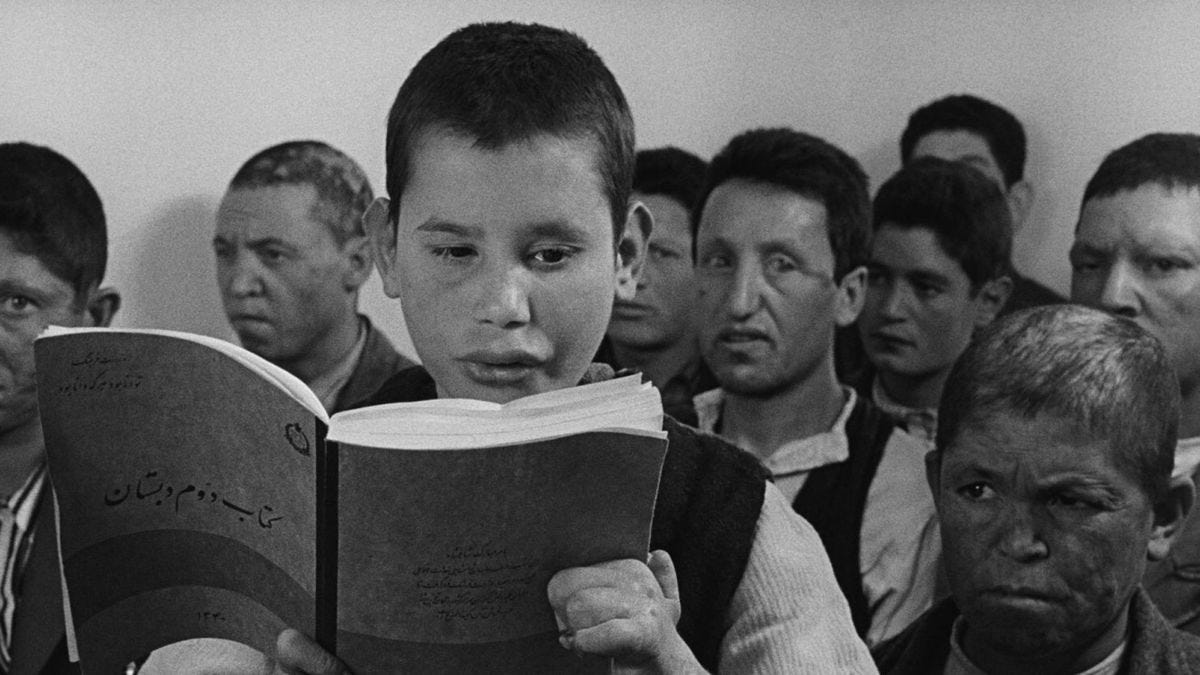

The House is Black, F.F. Zad (1962)

“Radical empathy” is how I’d describe F.F. Zad’s documentary short set at a leper colony. It was her only film, she passed a few years after its completion, and I can’t think of a filmmaker whose sole film, featuring unbridled pathos, has touched me more deeply.

Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, Chantal Akerman (1983)

I recently wrote about my experience seeing Jeanne Dielman in a theater, so I won’t belabor the point other than to say that the potato peeling scene is one of the most dramatic scenes I’ve ever witnessed.

Killing Time, Fronza Woods (1979)

Few films have captured suicidal ideation with as much care, nuance, and humor as Woods’ modest vision, which she stars in under the pseudonym of Sage Brush. In considering the perfect outfit to die in, Sage ruminates on the complexities of life, thereby becoming life-affirming.

Kwaku Ananse, Akosua Adoma Owusu (2013)

Filmed in Ghana, Owusu’s short sees a young woman returning home for the funeral of her father only to be drawn to the woods by his ghost. Interwoven with personal memories, local folklore, and emotional ghosts, the director’s rich, lushly composed fable is spellbinding in its reconciliations between grief and anger in the face of complicated loss.

Matchstick Men, Ridley Scott (2003)

A dark comedy led by Nicolas Cage as a con artist with tourette's syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder who discovers he might have a 14-year old daughter (Alison Lohman), file this under the oddball star-vehicles that aren’t made anymore. Deliberately plotted, and at times, elaborate in its filming and in the choses both Cage and Sam Rockwell, as a fellow con man, make, this is Scott’s most unusual film.

Near Dark, Kathryn Bigelow (1987)

Bill Paxton is a ball of sweat, grime, blood and manic energy as a trigger happy vampire among a cadre of blood suckers taking in a new member to their order as they traverse across the Midwest. While this tactile children of the night tale features a touching romance and big explosions, they can’t tamp down Paxton from being the focal point of the rampaging action.

Night of the Comet, Thom Eberhardt (1984)

This Los Angeles set, post-apocalyptic sci-fi zombie concoction was actually the first film I watched in 2022. Two sisters band together after a deadly comet not only eviscerates everyone they know, but turn some into brainless flesh eaters. Catherine Mary Stewart and Kelli Maroney are transfixing in their courageous yet relaxed rendering as teenage girls at the brink of extinction.

Opening Night, John Cassavetes (1977)

There’s a moment where Gena Rowlands, playing an actress struggling to grasp her part as production moves closer to opening night, that has remained with me throughout the year. She talks about how when she was younger her emotions lived so close to the surface that it took very little effort to scratch them. Now she has to work. If that isn’t a metaphor for writing, vocalizing the worry I experienced regarding the potency (or lack thereof) of my words during the past year, I don’t know what is.

Orlando, Sally Potter (1992)

A repertory screening at Virginia Film Festival, Sally Potter’s queer manifesto sees Tilda Swinton portraying an immortal Elizabethan noble who traverses eras, politics and genders, with a curiosity and glee that makes this film as effervescent and groundbreaking of a watch, today, as it was 30 years ago.

Out of the Past, Jacques Tourneur (1947)

Robert Mitchum, portraying a former crook living in a small town under an assumed name, has it all: the girl (Jane Greer), respectability, a network of friends — but it’s all thrown in jeopardy when his former partner, played by a demented Kirk Douglas, arrives to reclaim his money and his girl (Mitchum was hired to find her, but has instead fallen for her). Everyone in this film is operating on the highest level: from the adept actors, working with characters who fit like a glove, to the sulky cinematography.

Paisan, Roberto Rossellini (1946)

My favorite of Roberto Rossellini’s pictures is Paisan, an omnibus of World War II stories set in the rubble of post-war Italy, that acutely apprehends the devastation — both physical and societal — wrought upon the survivors living in the remnants of their previous world. It’s a film that clearly influenced Spike Lee’s Miracle at St Anna — the director for reason still unbeknownst to me, thought the material possessed some comedic value — but still stands as Rossellini’s most emotionally accessible film.

Red Desert, Michelangelo Antonioni (1964)

Of the four collaborations between Monica Vitti and Michelangelo Antonioni, Red Desert is probably my favorite. Their only work together in color, Antonioni hit the peak of capturing Vitti’s uncanny elusiveness in this picture about and a mother and son wandering an industrial wasteland. Though filled with smog and smokestacks, the auteur understands the urban beauty these blots the landscape can have a gorgeousness, an enrapturing aesthetic that often reminded me of my childhood.

Le Samouraï, Jean-Pierre Melville (1967)

Alain Delon has never looked cooler, or more in control than as the methodical hitman in Le Samouraï. Smart characters, a catchy jazz score, eloquently composed shadows, combining for endless suspense — keeps one enraptured by its atmosphere until the final poetic shot. It is among the gold standards of noir.

The Seduction of Mimi, Lina Wertmüller (1972)

It unfortunately feels as though an appreciation of Wertmüller’s style and comedic sensibilities have fallen by the wayside. Maybe it’s because her silliness is viewed as being too exaggerated? Maybe it’s because her humor thrums on a subversive kind of irony? In any case, The Seduction of Mimi, set around a buffoonish laborer and womanizer (Giancarlo Giannini), is the director’s most politically savvy yet stylish work.

Umberto D, Vittorio De Sica (1952)

The only film more heartbreaking than Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves is De Sica’s Umberto D, wherein a destitute elderly man must choose between supporting his cute dog and his own physical and financial health. It’s another picture that demonstrates the inequities of our society: flawed governmental safety nets, apathy toward the elderly, and pernicious landlords—that never feels cloying or manipulative. And it features an absolutely devastating final shot centering this man and his dog.

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, Jacques Demy (1964)

Even with his release of Babylon (a film I love) I’m not sure I’ll ever fully forgive Damien Chazelle for ripping off the ending to The Umbrellas of Cherbourg with La La Land. Like that film, Umbrellas, a musical, concerns two star-crossed lovers who by circumstances outside of their control are eventually put to a brutal test. Technicolor has rarely looked as gorgeous as here, adorned with pristine lighting and vibrant costumes. The conclusion, with Chazelle lifted without imbuing his version with remotely the same thematic heft, is an all-timer for the dreamers.

My watchlist is becoming unwieldy reading your lists though I’ve seen a few. Still will need to clone myself! Le Samouraï is a favorite of mine too.

Great list!